In the late afternoon sunlight of a high-altitude flight, Frank White gazed out the airplane window at the patchwork of the American landscape far below. It was the early 1980s. White—a self-described space philosopher—found himself mesmerized by the sight of Earth from 30,000 feet. As a boy, he had imagined leaving Mississippi to become an astronaut. Decades later, as a Harvard-trained thinker in his forties, he searched for ways to advance humanity’s future in space. He would have to do it without a rocket or an engineering degree.

Pressing his forehead to the glass, he watched the curvature of the horizon. White experienced a flash of insight. People living permanently off the planet would always see Earth as a whole. They would constantly perceive what astronauts only glimpse during missions. Earth would appear as a radiant blue sphere amid darkness, its lands and weather systems all interconnected. “They would experience the overview effect,” he realized, coining a term for a profound shift in perspective.

A Boy with Cosmic Ambitions

White’s fascination with space took root almost as soon as he could talk. Family lore holds that by age four, White was already babbling about leaving Earth to live on other worlds. By age ten, he devoured an astronomy book his mother gave him. He even began launching homemade rockets in the backyard. When those DIY missiles fizzled, young Frank sought expert guidance. Undeterred, he wrote to Wernher von Braun, America’s leading rocket engineer. He asked how he could become a “rocket scientist” himself. To his astonishment, von Braun replied with friendly advice: study plenty of math, chemistry, and physics. He even included autographed NASA photographs. White treasured the response. Years later, he would joke that those subjects weren’t his strong points.

As a teenager in the early 1960s, White set his sights on becoming an astronaut. He earned an appointment to the U.S. Air Force Academy—a coveted ticket to the stars. Meanwhile, a wise high-school counselor urged him to also apply to Harvard. To White’s surprise, Harvard offered him a full scholarship. Suddenly he faced a fork in the road. One option was the disciplined pilot’s path to space. The other was an academic journey that played to his aptitude for big questions. After much deliberation, he chose the life of the mind. Hearing that at Harvard “the life of the mind was honored” above all helped tip the balance. Advanced calculus and flight training had their appeal. But White sensed his strengths lay more with philosophy and social science than with aeronautical engineering. He matriculated at Harvard, then went on to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, trading a flight suit for academia.

The choice proved pivotal. Watching the Apollo 11 Moon landing from Oxford in 1969, White felt a pang of wistfulness. He had diverged from the astronautical route. But he also sensed that he could contribute to the space endeavor in a different way. Instead of strapping into a capsule, he would grapple with the conceptual and ethical questions of exploring the cosmos. Years later, that path led him to articulate a new idea that would reframe how humanity thinks about Earth and space.

The Flight That Launched an Idea

White spent the 1970s and early ’80s finding his niche in the space community. Aerospace conversations were dominated by engineers and test pilots, but White carved out a role as an intellectual synthesizer. He obsessed over what daily life would be like for those who might call a space colony home. That question literally took flight on one cross-country trip. In the early ’80s, while flying from Boston to California and mulling over O’Neill’s ideas of off-world settlements, White felt two trains of thought converge. Looking out at the continent from high altitude, he had a revelation. People living permanently off Earth would constantly have an over-arching view. They would always see our planet as one integrated system, without the artificial boundaries visible on maps. In that moment, White grasped that such a perspective could fundamentally alter one’s consciousness. People living off the planet would always have an overview. They would experience something profound – an overview effect.

Eager to explore this epiphany, White began testing the idea by talking to those who had come closest to that vantage point: astronauts. In the absence of anyone actually living in space long-term (the International Space Station didn’t yet exist), astronauts served as his proxies for understanding the psychological impact of seeing Earth from above. To his intrigue, many astronauts indeed struggled to articulate the awe they felt when looking back at their fragile home planet floating in the void. They spoke of a newfound sense of unity and an urgent desire to protect the planet. These feelings went beyond anything their training or mission briefings had prepared them for. It was as if the ancient Copernican shift – the realization that Earth is not the center of everything – was happening inside the minds of modern spacefarers.

From Book to Movement

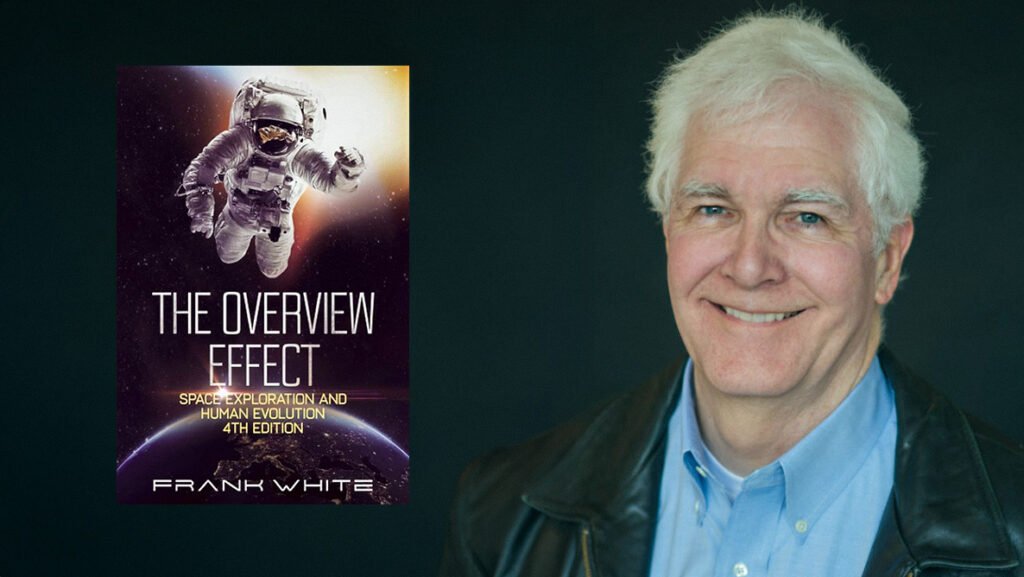

In 1987, White distilled these insights into a book titled The Overview Effect: Space Exploration and Human Evolution. He hoped the book would spark what he boldly called a conceptual revolution in how people see our world. “What I wanted was a revolution,” White says of his mindset at the time. Not a political or violent upheaval, but a shift in awareness – a peaceful turning point in the human story. By examining astronauts’ testimonies, he aimed to show that the Overview Effect was more than just an astronaut’s anecdote. It was a glimpse of what might happen if humanity as a whole adopted a planetary perspective.

At first, that revolution was slow in coming. The book attracted a niche audience among space enthusiasts but did not burst into the mainstream. White continued writing and speaking, patiently refining his ideas. For two decades, he sometimes wondered if the world would catch up. “I spent 20 years thinking the revolution was not going to happen,” he admits. The original Overview Effect book eventually went through second and third editions in the 1990s and 2000s. This happened largely thanks to allies at NASA who believed in its importance. Even so, it remained under the radar.

In 2007, White got his first hint that the tide was turning. One colleague organized a small conference on the Overview Effect to mark the book’s 20th anniversary. To White’s surprise, about a hundred people gathered – former astronauts, scientists, artists, and philosophers – drawn by the concept. Person after person stood up to tell him that his idea had changed their lives. “The Overview Effect is the most important book I ever read,” one attendee said. White was floored. He had never before seen concrete evidence that his once-obscure notion was quietly spreading and inspiring a community.

Buoyed by this realization, White and a few collaborators founded the Overview Institute in 2008. The Institute became a hub for research and advocacy around the perspective shift of seeing Earth from space. It brought astronauts together with educators and even virtual-reality designers, all evangelizing this perspective shift as a key to solving problems on the ground. What began as one man’s idea was evolving into a social movement of sorts. White noted that something bigger than all of them seemed to be at work, and he focused on helping it unfold.

Over the years, the term “overview effect” seeped into the culture of space exploration. Seasoned astronauts routinely reference it in interviews. Space tourists hear it touted as a life-changing perk of suborbital flights. In 2021, when billionaire Jeff Bezos went to space, he said he wanted to experience the Overview Effect. It was a sign that White’s once-esoteric term had entered the mainstream lexicon. Environmentalists and philosophers have also embraced the concept as a way to inspire global unity and ecological stewardship. In White’s view, this is the ultimate goal. It’s not just that individual astronauts come back enlightened. Society at large must absorb that perspective.

The Zen of Earth-Gazing

Communicating the ineffable has been a challenge for White from the start. How do you convey in words an experience that is literally beyond words? To bridge that gap, White often reaches for analogies to spiritual insight. He notes that describing the Overview Effect to someone who hasn’t been to space is difficult. He likens it to trying to explain a Zen koan. Intellectual understanding only goes so far; direct experience is transformative. White’s conversations with astronauts over the years have convinced him of one thing. Seeing Earth from space triggers something akin to a meditative revelation. It creates an awareness of the unity and fragility of all life.

Yet White stops short of framing the Overview Effect as a mystical epiphany. He is careful to describe it in human terms – a cognitive shift that arises from a better context, not a supernatural vision. In his gentle, thoughtful way, he sometimes suggests that Earth itself serves as a kind of teacher when seen from space. Astronauts return not with cosmic secrets, but with a renewed sense of responsibility and wonder. That outcome, White argues, is profoundly human – and necessary. He believes this mental shift can be “brought down to Earth” through various means—education, art, even immersive simulations. All these, he thinks, can help spark a broader change in how we treat one another and our planet.

White’s own style in discussing these lofty ideas is notably down-to-earth. Colleagues say he listens more than he pontificates. He often pauses mid-thought, searching for the precise way to articulate something that resists easy description. In one talk, he quipped that the Overview Effect might best be treated like a riddle or a poem. It was something to be experienced, not just defined. That reflective, almost Zen-like manner has become a hallmark of his interviews and lectures. It sets him apart from more bombastic space visionaries.

Curiosity at the Fringes

While the Overview Effect has been White’s calling card, his intellectual curiosity roams far beyond that single idea. He has never been afraid to explore subjects that mainstream space thinkers sometimes avoid. Take UFOs, for example. “I have been studying UFOs since I was 10 years old,” White admits cheerfully. Decades before governments began releasing files on unidentified aerial phenomena, White was already studying the mystery. He approached it with a mix of open-minded interest and skepticism. In 2021, when the Pentagon issued a much-publicized report on UFO sightings, White read it closely. He wryly pronounced it a triumph of Zen expression. The document managed to say a great deal while ultimately saying nothing definitive.

This willingness to entertain unconventional topics comes from the same wellspring as White’s Overview Effect work. It reflects a profound curiosity about the unknown. In the 1990s, he even teamed up with science-fiction legend Isaac Asimov to co-author books speculating about the future. Asimov was impressed by White’s knowledge and insisted that White share the byline rather than just ghostwrite. It was a gesture of generosity White never forgot. The through-line in all these pursuits is White’s insistence on looking at the big picture and asking “what if?”, while still grounding ideas in thoughtful analysis.

A Quiet Evangelist

Despite his far-reaching visions, those who meet Frank White are often struck by his modesty and approachability. Now in his late seventies, he carries himself with the calm of someone who thinks in decades, not news cycles. White is quick to credit others and rarely seeks the spotlight for himself. He co-founded organizations like the Overview Institute and the Human Space Program to keep the focus on ideas. He wanted it not to center on any one individual. The Human Space Program is a nonprofit initiative. It aims for the sustainable, ethical, and inclusive evolution of humanity into the solar ecosystem.

“Successful people are often quite humble and very generous to others,” White has observed. It’s a lesson he learned early on from mentors like Asimov. Whether he’s interviewing astronauts or brainstorming with colleagues, he is known for listening thoughtfully and giving credit where it’s due. Those around him find it refreshing – the visionary “space philosopher” remains remarkably down-to-earth in conversation.

His home base is Massachusetts, just outside Boston. There, he enjoys a grounded family life with his wife Donna, five grown children, and a growing constellation of grandchildren. (Yes, the Overview Effect guru has his own crew on spaceship Earth.) One moment, he might be Zooming into a space conference to discuss long-term settlement strategy. The next, he’s taking a grandchild out for ice cream. The cosmic and the quotidian coexist comfortably in his life.

Although some people call him the “father of the Overview Effect,” White prefers to see himself as a messenger or facilitator. The idea, he insists, was ready to be discovered – it just happened to land in his lap during that fateful airplane flight. Ever since, he has felt an obligation to share it. “You have to trust the process,” he likes to say about following big ideas where they lead. That process has led him to become an unlikely sort of evangelist. He speaks softly, asks questions, and invites others to imagine along with him.

Earth, Space, and Human Destiny

When Frank White considers the future, he doesn’t focus on gleaming starships or technical feats. He focuses on the evolution of human perspective. Ask him about humanity’s destiny in space, and he will start with Earth every time. Before we can successfully spread into the cosmos, White argues, we need to grow up as a species here at home. He hopes the Overview Effect can accelerate that maturation. If more people, through space travel or even vivid simulations, internalize a unified view of Earth, it could spark what he calls a socially conscious overview. This would mean a collective shift in how we conduct our politics, economics, and caretaking of the planet.

Only on that foundation, he believes, should we launch fully into a multi-planet civilization – and White thinks we will. In fact, he envisions a time when large numbers of people live beyond Earth. They would do so not to abandon our home world, but to help save it. “Leaving the planet is not abandoning it. It’s an act of love,” he explains. The burdens on Earth are great. Moving some of our population and heavy industry into space could give the planet breathing room to heal. It’s a bold proposition: transform humanity into a spacefaring species as a form of environmental therapy for Earth. White knows the idea can sound fantastical or even quixotic. But he points out that just a few decades ago, the notion of private citizens riding rockets to orbit seemed like science fiction. Times change, and so do perspectives.

Even as he sketches out these grand possibilities, White remains mindful of the practical steps needed. He speaks of international cooperation and ethical guidelines, emphasizing that expanding into the solar system must be an inclusive venture. It cannot become a new arena for old conflicts. His dream is a “Human Space Program” – an umbrella project for all of humanity, transcending nations. It would coordinate our growth into the cosmos responsibly. If that sounds utopian, White is undeterred. He’s spent a lifetime nurturing an idea that many once dismissed as airy idealism. Now he has lived to see astronauts, entrepreneurs, and scientists embrace it in earnest.

In his eighth decade, White still hasn’t given up on experiencing the literal Overview Effect himself. In 2021, he entered a contest for a seat on SpaceX’s Inspiration4, the first all-civilian orbital mission. He hoped to finally see Earth from orbit with his own eyes. He didn’t win a spot. It was another reminder that his role in this story may always be from the ground. He might forever be championing a vision rather than taking the ride – and that’s alright. As White often emphasizes, the Overview Effect is ultimately not about one person’s journey. It’s about a perspective that belongs to all of us.